...The woman wrote in her complaint that she was afraid to go to work or to the grocery store and that Officer Rojas had warned her: “‘I will make sure that you wish you were dead when I finish with you, and there is nothing you can do to protect yourself. Remember I’m a cop. There is nowhere you can hide. I will make your every day a living hell'"...

RECORDS SHOW ASPECTS OF OFFICER’S PAST ARE ‘SCARY’: 700 PAGES OF MEMOS AND INTERVIEWS ON ALLEGATIONS AGAINST ROJAS

Telegram & Gazette

By Thomas Caywood

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Worcester — Tucked among 714 pages of memos, interview transcripts and other police records detailing allegations of misconduct against Officer Mark A. Rojas is a stack of his handwritten poems provided to police investigators by a former girlfriend in fear for her life.

I’ll kill you …

I’ve done so in my dreams.

I’ve killed you …

I watched you die …

And heard your screams.

That chilling verse opens the first poem in the stack.

It was penned at least seven years ago and filed away by the Police Department while Officer Rojas continued to patrol city streets with a badge and a gun. During that period, a number of additional citizen complaints of police brutality and other serious misconduct were lodged against him.

“If a student wrote a poem like that in school, he’d be suspended immediately. That’s scary,” said Howard Friedman, a Boston lawyer who has specialized in police civil rights litigation for 25 years. “And if a police officer is abusive toward former girlfriends, that’s an indication of how he will treat civilians he doesn’t even know.”

The poem was among hundreds of pages of documents, comprising four separate cases of alleged misconduct, recently turned over to the Telegram & Gazette to settle the newspaper’s yearlong lawsuit against the city seeking release of the records.

The previously secret documents show that police administrators allowed Officer Rojas to continue serving on the force during the tenure of three chiefs and one acting chief as citizen complaints mounted and the department’s own Internal Affairs division repeatedly raised serious concerns about his character and fitness for duty.

Investigators documented evidence in the four cases that Officer Rojas had choked a man involved with the mother of one of his children, held a handcuffed prisoner while an off-duty officer struck the man in the head, lied to cover up that assault and other misconduct, used his position to run police background checks on women and romantic rivals, and posed a “genuine threat” to the ex-girlfriend who turned over the poems.

His superiors forced the officer to surrender his service weapon and personal firearms — three handguns and an AK-47 military-style “assault rifle” — two previous times before Chief Gary J. Gemme last year permanently stripped him of his license to carry firearms.

But Officer Rojas remains on the city payroll drawing an annual salary of $73,000 although he has been out on disability for more than a year with a reported ankle injury.

The four recently turned-over misconduct cases represent only a small fraction of Officer Rojas’ lengthy Internal Affairs file, which numbers 15 cases and more than 1,500 pages. The T&G previously has reported on six other closed cases containing more than a dozen specific allegations of misconduct ranging in severity from discourtesy to assault and battery.

Chief Gemme has not signed off on the final reports in five other misconduct investigations against Officer Rojas, meaning they technically remain active investigations and thus are protected from release to the public under the state Public Records Law.

As has been his practice in recent months, Chief Gemme did not respond to or acknowledge requests for an interview made through his spokesman, Sgt. Kerry F. Hazelhurst, and through City Hall.

However, Chief Gemme’s boss, City Manager Michael V. O’Brien, defended the city’s handling of Officer Rojas.

“We’ve acted prudently, working within very rigid parameters of contract language, human resources policy and law, and I believe those efforts have the matter close to final resolution.”

Mr. O’Brien did not specify what he expected that resolution to be.

The former girlfriend who received the threatening poem, whose name was removed from the records before they were turned over to the T&G, told Internal Affairs investigators that Officer Rojas had pledged to make her life a “living hell” and repeatedly threatened to kill her and a new man in her life.

The woman wrote in her complaint that she was afraid to go to work or to the grocery store and that Officer Rojas had warned her: “‘I will make sure that you wish you were dead when I finish with you, and there is nothing you can do to protect yourself. Remember I’m a cop. There is nowhere you can hide. I will make your every day a living hell.’”

Police officials sent then-Lt. Paul B. Saucier, head of the vice and gang units at the time, to Officer Rojas’ home to confiscate his personal firearms during the investigation.

In a memo to then-Chief Gerald J. Vizzo, a senior Internal Affairs investigator informed the chief that he and another investigator “are of the opinion that the complaint is credible, and that Rojas represents a genuine threat to the safety” of his ex-girlfriend.

The investigation, labeled Case 2 by the police department, began under Chief James M. Gallagher, who retired in September 2003, and continued during the tenure of Chief Vizzo, who retired in December 2004.

It isn’t clear from the records which of the city’s recent chiefs of police signed off on the final report. Despite the threatening poem and the opinion of the investigators that the woman was in danger, however, her complaint that she and her boyfriend had been threatened ultimately was deemed “not sustained” — a police term meaning the investigation did not find sufficient evidence to prove or disprove her allegations.

A memo dated July 24, 2003, notes that Officer Rojas’ AK-47 and three handguns, as well a box of 7.62 mm military-grade ammunition for the rifle had been returned to him.

Of the allegations in that case, the only one sustained by the police department was that Officer Rojas had illegally conducted a criminal background check and disseminated the results. It can’t be determined whose record he checked or to whom he passed the information.

Another of the recently turned-over misconduct investigations, labeled Case 9, also occurred during the tenure of former Chief Vizzo, meaning it dates back at least to late 2004.

The heavily redacted report states that “it is certainly reasonable to conclude” that Officer Matthew Coakley, who was off duty at the time, hit a handcuffed prisoner in the side of the head outside a Main Street nightclub while Officer Rojas, who was working a paid detail, stood by.

The report attacks Officer Rojas’ claim that he did not see anyone strike the prisoner, noting that when questioned by Internal Affairs investigators he sat slouched in his chair, gave vague answers or claimed not to recall even the most basic details of that night.

“Even more disturbing,” the report states, “other answers appear to have been outright fabrications, such as when he stated he did not speak to staff members of (redacted) after the arrests were made, although several of the witnesses, including the independent witnesses, not only stated he went over to talk with the staff, but that he actually shook hands with them as well.”

The section of the lengthy report dealing with Officer Rojas’ conduct concludes: “Thus, it has become obvious that it is more probable than not that Officer Rojas either failed to cooperate with the investigation by not being forthright in his answers, or that he just simply refused to tell the truth.”

Allegations that Officer Rojas failed to submit his report to Internal Affairs on time and that he lied to investigators were both sustained.

It wasn’t the last time investigators from Internal Affairs, which was later renamed the Bureau of Professional Services, questioned Officer Rojas’ truthfulness.

In the probe labeled Case 1, a report dated June 21, 2005, and addressed to Chief Gemme covers allegations that Officer Rojas angrily confronted an ex-girlfriend’s husband and then jumped into his car and began choking him as the man called 911 for help.

It is not possible to tell from the redacted files if the female complainants in cases 1 and 2 are the same person.

Officer Rojas, who was again stripped of his weapons, denied choking the man and told investigators that the car began to move and, for fear of being run over, he jumped into the vehicle.

Chief Gemme ultimately sustained the allegations of assault and battery, conduct unbecoming a police officer, untruthfulness and illegally conducting a criminal records check against Officer Rojas.

The chief added a handwritten note next to his signature instructing investigators to “Please submit addendum to this report to ascertain truthfulness by Rojas in the original reports.”

The follow-up investigation into whether Officer Rojas perjured himself in a sworn deposition resulting from the incident produced a second report signed by Sgts. John J. Cronin and Michael J. Kwederis of the Bureau of Professional Services.

The investigators reported to the chief their findings that Officer Rojas’ “capacity for veracity is limited, at best.”

Chief Gemme signed off on those findings as well.

But, once again, Officer Rojas was allowed to continue his law enforcement career.

Mr. Friedman, the lawyer specializing in police misconduct cases, said there can be no excuse for not moving aggressively to fire any officer found to have lied in the course of his or her duties because such officers can’t be trusted to testify truthfully in court. An officer shown to have lied in the course of his or her duties could undermine efforts to prosecute anyone he or she arrests, he noted.

“You have to look for repeated complaints, even if you didn’t sustain the complaints. It’s true in most departments, and I’m sure it’s true in Worcester, that most officers go through their careers with zero or one Internal Affairs complaints against them,” he said. “If you have numerous complaints against an officer like this, something is wrong.”

Although the names and most dates have been redacted from the file, the details in Case 1 match an incident involving Officer Rojas that previously came to light because it went to court.

In June 2005, Central District Court Judge David Ricciardone found Officer Rojas guilty of assault and battery for choking his ex-girlfriend’s husband, J. Gregory Harding.

The judge sentenced the officer to seven months of probation and ordered him to attend anger management classes for his temper. The guilty verdict was set aside a few months later, however, when Mr. Rojas’ lawyer convinced the judge to order a new trial.

That defense lawyer was Joseph D. Early Jr., the current Worcester district attorney.

The case then was continued without a finding in March 2006 after Officer Rojas maintained his innocence, but admitted in court that there was enough evidence for the prosecutor to get a conviction — a common legal maneuver called an Alford plea.

In the criminal case against Officer Rojas, Mr. Harding alleged that the policeman jumped into his car in September 2003 and refused to get out. Mr. Harding said he called 911 on his cell phone, and Officer Rojas reached over and started choking him as he screamed for help into the phone.

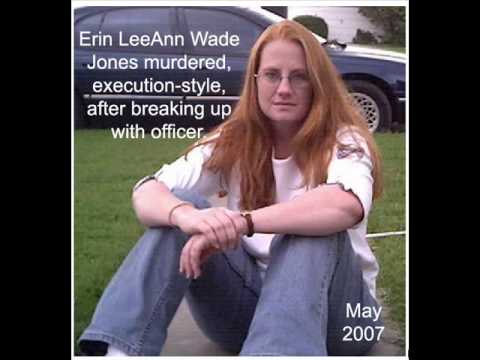

The last of the four previously undisclosed files, labeled Case 8, involves a complaint against Officer Rojas lodged with the Bureau of Professional Services on May 23, 2007.

A man complained that Officer Rojas, who had previously arrested him and was now dating his ex-girlfriend, had verbally harassed him. The man’s name is redacted from the files turned over to the T&G.

Once again, investigators found that Officer Rojas had used his position as a police officer to pull the man’s criminal record without justification. And once again, Officer Rojas continued to serve as a police officer despite the finding.

“That’s a violation of law. That’s real easy. If you are accessing somebody’s criminal history for the purpose of personal reasons, that’s a violation of the law,” said retired state police Col. Reed V. Hillman, who lead that agency from 1996 to 1999.

Chief Gemme has said in previous interviews that union contracts and state civil service rules make it difficult to fire rogue officers.

Mr. Hillman, who had a reputation as a reformer during his tenure as the leader of the state police, and who went on to run for lieutenant governor as a Republican, agreed that firing bad cops is difficult.

“The world is run by public sector unions. You’re a police administrator trying to do the right thing, but in many cases you’re ability to do the right thing is severely limited by the civil service rules,” he said.

But Mr. Friedman offered a different view.

“It’s hard to be a police administrator, but to say you can’t discipline anybody isn’t true,” he said. “It’s a self-defeating theory. What I often see is they say, ‘Oh, we can’t get rid of them,’ so they don’t even try. It’s a question of having the will to really go about doing it.”

One point on which the veteran police misconduct lawyer and former state police colonel agree is the seriousness of any allegation of police brutality, such as those repeatedly lodged against Officer Rojas during his 13 years on the street before going out on disability.

“There’s nothing that we would rather do than take care of a bad apple amongst us,” Mr. Hillman said.

While sustaining a complaint of police brutality against an officer makes it difficult from a legal standpoint to defend against a lawsuit in which the state or city may have to pay tens of thousands of dollars to settle, the alternative is worse, he said.

“You’re going to be paying a lot more if you get hit with a ‘failure to train and supervise’ complaint,” Mr. Hillman said. “You have to be able to show you’ve been taking these kinds of complaints seriously. Otherwise, you’re cutting a huge check. It’s more cost effective to deal with each incident.”

Contact Thomas Caywood by e-mail at tcaywood@telegram.com.

[Full article here]

[police officer involved domestic violence oidv intimate partner violence (IPV) abuse law enforcement public safety fatality fatalities lethal teflon hx repeat massachusetts state]

What a peach.

ReplyDelete